Research has shown that job switching leads to higher wages, and the Great Recession supercharged this trend with job switchers seeing real wage growth in 2022. Our new research shows that whether jumping ship will pay off also depends on where a worker falls in the income distribution. Loyalty pays for a strong majority of jobs paying $75k or less (77%). However, for higher paying roles (over $125k), it rarely does: in 83% of job groups, workers with longer tenure earn no more than newly hired but comparable employees — and in 30% of high paying roles, longer company tenure is associated with lower earnings, all else being equal.

This has implications with the wave of pay transparency legislation that is starting to play out across the U.S. Particularly for higher-paying roles and corporate support positions, it’s likely that the stated ranges in job listings are going to be high relative to the pay of long-tenured employees. Dig into the research to find out why new hires get paid more — and what employers should do if they want their pay structures to reward job loyalty.

Why would wages ever be higher for new hires?

We recently conducted a deep-dive pay analysis of a well-paid, mid-level professional position for one of our clients. What we found was striking. For employees hired more than two years ago, there’s a clear upward association between pay and tenure — workers with at least 10 years with the company earned 9% more than workers in similar positions with 2-4 years of service. However, employees hired over the past 12 months earned almost as much as employees who had been with the company for more than 10 years. The lowest paid set of employees were those in between. Those who joined the company two to four years ago earned on average 4.4% less than their peers.

Our customer was alarmed but not surprised by this finding. The job market has been so competitive for the past two years and they knew they were making aggressive offers to land the right candidates. They also knew that their salary budgets for tenured employees were not keeping pace with offers in the market. Even though they understood why, the result — a compensation system that no longer rewarded loyalty to the company — was not what they wanted.

This customer wasn’t the only one to face the twin forces of a competitive job market and tight salary budgets, so we decided to test whether the same trend was playing out in different job groups at different companies. We found some clear patterns. While frontline and lower-paying roles consistently tend to reward longer-tenured employees more than their newly hired but comparable peers, this is true for only one out of six higher-paying job groups.

New hires tend to earn more — in some jobs

We analyzed pay equity analyses conducted over the past year from 48 organizations, representing 786,000 employees across 1,716 distinct job groups. Job groups are composed of similar roles — meaning those with similar skills, effort, responsibility and working conditions. These pay equity analyses test for gender-based patterns in pay after controlling for neutral, job-related controls that can explain differences in pay — like location, management responsibilities, and tenure.

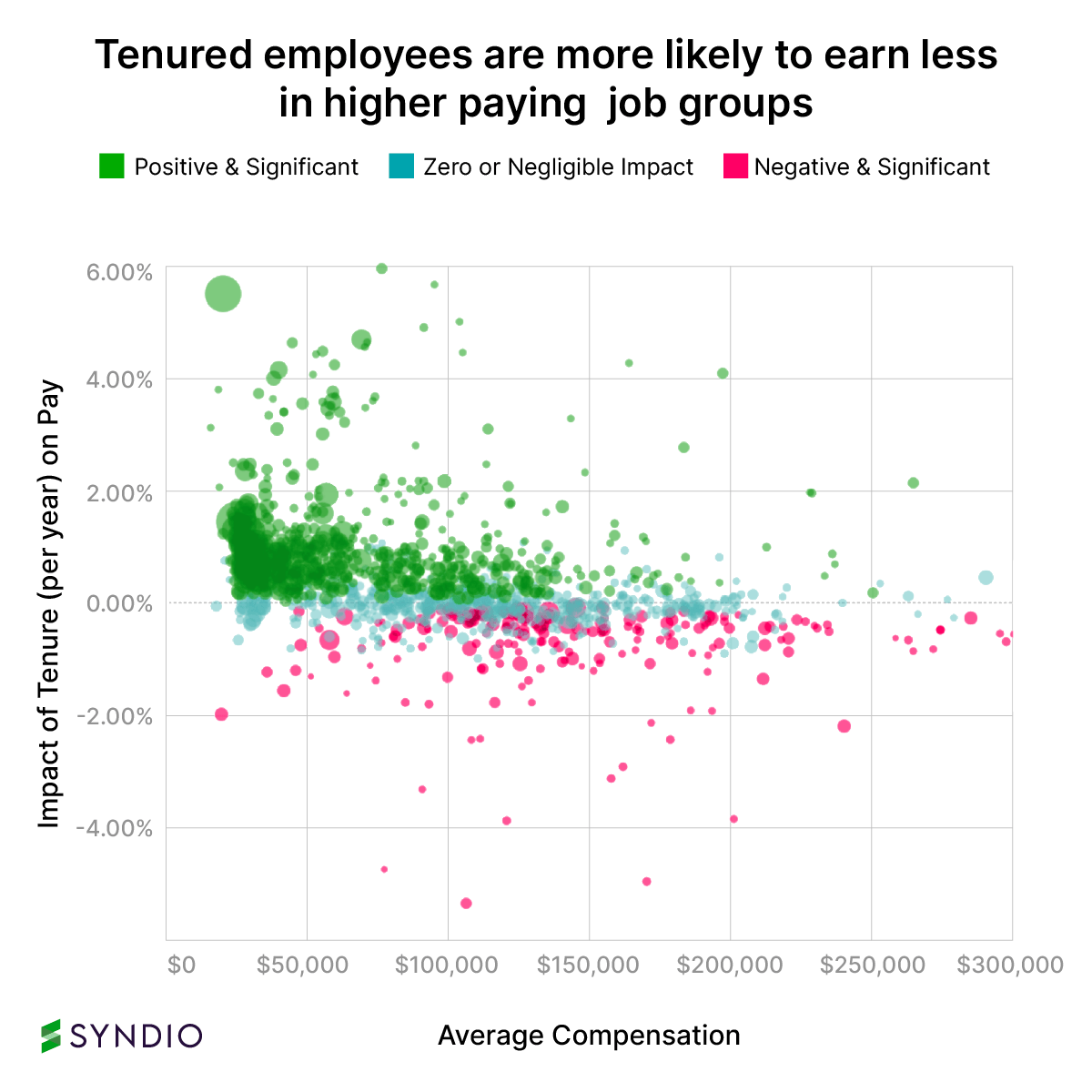

In our analysis, we reviewed the impact of pay in each of those job groups. We split the effects into three buckets: positive and significant, negative and significant, and zero or negligible impact. We also split the job groups based on their average earnings and by job type.

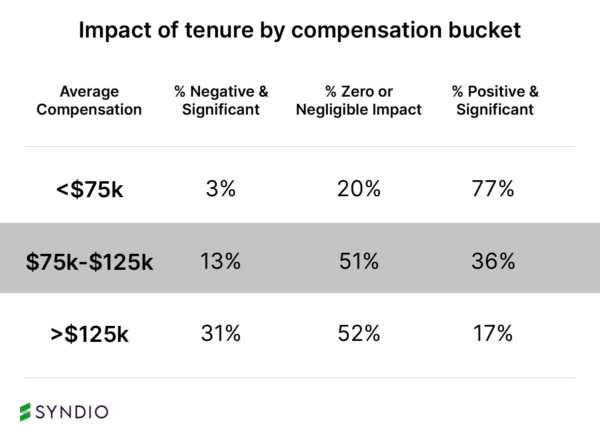

The plurality of job groups (48%) do have a positive association between tenure and pay, while 39% have zero or negligible impacts and 13% have a negative association. Positive results become less common and negative results more common as we move into higher earning groups.

We saw the greatest difference in impacts when we categorized the job groups by average earnings. In the lowest earning job groups, 77% had a positive association between company tenure and pay, while 20% had no discernible impact and 3% had a negative impact. The highest paying job groups — those with average earnings over $125,000 per year — were much more likely to have no impact or even a negative impact: tenure had a positive impact in only 17% of these groups, while it had no discernible impact in 52% and negative in 31%.

Frontline roles have patterns very similar to the lower-paying job groups — 78% have significant and positive relationships, 21% have zero or negligible relationships, and only 1% have a significant and negative relationship between tenure and pay. Corporate support roles (including HR, finance, marketing, IT, and analytics) are spread across the earnings spectrum, and are more likely to have negligible or negative results: 25% of these job groups show positive trends while 55% have zero or negligible relationships, and 20% have negative relationships.

Does your organization reward what you want it to?

Companies have different thinking about what they want to reward, and it may even vary by position. In high turnover positions where finding employees may represent a significant part of management’s role, incentivizing employees to stay makes sense. For other jobs, bringing in fresh perspectives from outside the organization is potentially valuable, so attracting these candidates with higher pay may make sense. This may explain why we see more mixed relationships in support and higher-paying roles than in retail, fulfillment, and other frontline positions.

The perfect storm of tight salary budgets and a very competitive labor market has put pressures on a pay-for-tenure strategy. If organizations are posting pay ranges that put tenured employees low in those ranges, those ranges are going to create friction. Remember, with pay, perception is reality: how employees feel about their compensation impacts their satisfaction with their employer and their desire to stay. Ultimately, organizations should have a clear point of view on what their compensation strategy is in key roles — and ensure that their outcomes reflect that strategy.

The pay transparency era requires a new mindset about pay and rewards. Companies need to ask themselves, “Fundamentally, what do we want our current and prospective employees to think about how we pay them?” and then build a compensation program that reflects those goals. Get tips in this article on how to rethink your compensation strategy in the transparency era.

To dive deeper into this topic and offer practical advice, Syndio hosted a webinar featuring Dan Kuang, Director, People Analytics Equality at Salesforce. Watch Paying for Tenure: Does Your Organization Reward Loyalty the Way You Think? to learn best practices for creating a compensation strategy that is fair and equitable for both new hires and tenured employees.

Methodology

Virtually all of these job groups included additional controls in their statistical model. We excluded models with very low or very high R-square values. We split tenure effects into three buckets: positive and significant, negative and significant, and zero or negligible impact. The first two effects are related to whether the impact is statistically meaningful (having a p-value of less than 0.1) and the sign of the effect. For the third, we selected all results that were not statistically significant from zero, had point estimates that fell at least one standard error below an absolute value of 2%, and had a median impact of less than 3%. This approach excluded groups that were inconclusive due to large standard errors, or that were not statistically significant but still had substantial annual or typical impacts. We categorized job groups based on the name assigned. For example, job groups with “warehouse” in the name were assigned to frontline workers and fulfillment workers, while job groups with “talent” in them were designated as HR and corporate support workers. We reviewed the final job group categories after applying these word matches. Though many job groups remained uncategorized due to ambiguous or unclear job group names, they were still included in the average earnings divisions.