Today is Equal Pay Day in the U.S., a date that marks how far into the year the typical woman must work to finally earn what a man earned in 2022. Currently the typical woman earns somewhere between 77 cents and 84 cents on the male dollar, depending on labor force definitions. Pay inequity — women earning less for comparable work — is one cause of the gender pay gap, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. The pay gap is also significantly influenced by unequal opportunities for career advancement, particularly by promotion gaps.

Simply put, when women aren’t given the same opportunities as their male colleagues, they miss out on the career advancements that lead to higher pay, which can significantly impact their earning potential over time.

To shed light on this issue, we had the pleasure of interviewing Alan Benson, Associate Professor at University of Minnesota Carlson’s School of Management and expert in the econometric analysis of hiring, promotions, compensation, and incentives. His recent research “Potential” and the Gender Promotion Gap with Danielle Li (MIT Sloan School of Management), and Kelly Shue (Yale School of Management) shows that one of the underlying causes of the promotion gap is the subjective assessment of employee “potential.” Despite receiving higher performance ratings than men on average, women received lower potential ratings than men, which resulted in women being 13% less likely to be promoted than men.

We present the entire interview below (edited for clarity), but here are the key takeaways:

- Women are less likely to be promoted into manager and leadership positions, which is a major driver of the gender pay gap.

- At least some of the reason for this gap is bias in how managers assess womens’ “potential.” Women in particular are a third more likely than men to be rated as high performance but low potential.

- The most promising approach to achieving both efficiency and equity is not abandoning potential ratings altogether, but focusing on developing women who fall in that high-potential/low-performance box.

- This relates to other research showing the headwinds that women face in the workplace. Generally, business leaders need to take a more proactive approach to intentionally providing development opportunities. Dr. Benson put it well when he said, “By the time that you’ve arrived at the decision of who to give a shot in a role, it’s just too late.”

What is the gender promotion gap?

You, Danielle Li, and Kelly Shue have an excellent paper on the gender promotion gap. Tell us a little bit about your research, and how a promotions gap contributes to gender pay gaps at organizations?

The pay gap in 2022 was about 82%, meaning that women earned 82 cents on the dollar (compared to men) per hour worked. That’s the number if you look at the economy as a whole. But if an organization looks job by job for the people who are doing the exact same thing or who are nominally who have the same job or the same grades, that gap shrinks by quite a lot.

And so how do we put these two together? Well, it turns out that in organizations, a lot of the overall gap is explained by inequitable promotions — the tendency for women to be stuck in the lower rungs of the organization where they have lower average pay because they are less likely to be promoted up. You may have heard of this “glass ceiling” phenomenon where if you look within an organization, the shares of women who are the highest rungs of the organization decline — which are, of course, the more highly paid jobs.

If we really want to understand the gender wage gap in the whole economy, we have to understand why it is that women aren’t being promoted into these jobs and these levels that are associated with greater pay.

“If we really want to understand the gender wage gap in the whole economy, we have to understand why it is that women aren’t being promoted into these jobs and these levels that are associated with greater pay.”

How organizations rate performance and potential

In your paper, you discuss how assessing “potential” requires guessing how someone’s going to do a job that they don’t currently do. And that’s a tricky problem! One important part of your findings is that potential ratings strongly predict promotion probability, but that the link between potential ratings and actual future performance isn’t quite as strong. Can you briefly explain how the popular “Nine Box” rating systems work for assessing performance and potential?

In our paper, we were looking at data from tens of thousands of managers who manage subordinates and rate them using the widely-used “Nine Box” Assessment Planning tool. This tool is a grid in which immediate managers are essentially asked to pigeonhole their subordinates into one of nine boxes by rating them as high, medium, or low across the two dimensions of “performance” and “potential”. That 3×3 combination determines a lot about how the organization thinks you should be managed.

Nine Box is convenient because it’s not proprietary — it’s been around for about 50 years. Organizations can do it in an Excel sheet or they can build it out from any of the major HR information systems. The typical way that it works is the immediate manager rates you on one of these nine boxes, and then there’s a calibration meeting to try to level-set ratings for all of the subordinates. The scores are ultimately rolled up at an organizational level so that you categorize everybody into one of these nine boxes which then helps the organization determine who gets developmental opportunities and who gets promotions.

For example, someone who’s rated as a high performer but low potential would likely be kept in the same role to “keep doing their thing,” whereas someone who is rated high potential but medium performance, might be considered a good candidate for additional development opportunities and, ultimately, promotion into a more senior role where (according to Nine Box) their talents could be better served.

How might your results apply to organizations with other employee rating systems?

For organizations that use alternatives to Nine Box, whether that’s a 2×2 or a 5×5, and even if the terms are slightly different, they’re still essentially trying to evaluate subordinates on who is the best candidate for promotions and developmental opportunities.

This is an important function that organizations need to solve: Figuring out who are the best candidates for leadership roles. But they often resort to just asking immediate managers to rate their subordinates on potential, whether through Nine Box or some other ratings tool. .

Why is potential so hard to assess, and why might assessments favor men over women?

Our study looked at retail organizations, an industry where you can carefully track what the performance is in the future. For example, for department managers, you can track the performance of the department. What we found was that women were consistently underestimated in terms of their potential, meaning that when women who were rated as low potential got promoted anyway — which is a relatively rare scenario — their subsequent performance was actually considerably better than past ratings of their potential suggested.

“We found that women were consistently underestimated in terms of their potential, meaning that when women who were rated as low potential got promoted anyway — which is a relatively rare scenario — their subsequent performance was actually considerably better than past ratings of their potential suggested.”

Potential was correlated with future performance both within the same job and in future roles — but the overall rating level for potential was consistently lower for women than it was for men.

I think this really goes back to one of the main purposes of the Nine Box tool, that it’s a way of decoupling someone who’s a star performer in their current role from someone whose high potential suggests their contributions might be greater in a role higher up in the organization. Essentially, it’s a way to solve the Peter Principle problem, i.e. that organizations don’t necessarily want to take a star performer then turn them into a mediocre manager.

Potential approaches for addressing the gender promotions gap

Your paper discusses things that organizations might do to address this bias in potential ratings and promotions. You tested a few hypotheses, that female managers may be less biased against female employees and that the most effective managers may be less biased in their potential assessments. What did you find about these potential approaches for addressing the gender promotions gap?

I think there’s a lot of pet theories as to how organizations can better mentor and develop female women into potential leadership roles. One would be assigning women to other women managers under the assumption that women can serve as role models for other women, or would be less biased in their evaluations.

However, we don’t really find evidence that assigning women as female bosses in and of itself would do much to mitigate this issue. In particular, we found that while the gap between the ways that women rate men and women is slightly less biased, they simply rate everybody’s potential as lower than male managers do. The biggest gap, actually, — and where men benefit the most — is when men are rated by other men: They receive much higher potential ratings. And moreover, those are the groups that are most likely in the future to underperform the past ratings of their potential. So it seems that assigning women to female bosses isn’t going to be a silver bullet to getting women higher potential ratings and promotion opportunities.

Another alternative could be assigning women to the highest performing bosses. What we found here is that the bosses who were high performers themselves did give out higher ratings, but they were also more biased in those cases. So it seems that women didn’t really benefit from working under those high performing bosses either.

I think putting these two findings together, there’s not really a single quick fix in terms of how to check bias or reduce the gap in potential ratings between women and men just simply by assigning them to different managers.

You also test a couple of other scenarios, like removing potential ratings altogether and de-biasing the process by boosting the potential ratings of women with the highest performance scores. What did your analysis show for each of these scenarios?

We didn’t find very much evidence that just simply reassigning scores based on these easily observable factors would reduce bias. But we did do something called counterfactual analysis, which I think is similar to what you would find in software like Syndio’s where you test for bias and correct for it in some way. How can we change the ratings to achieve both equity and efficiency? Or in other words, is there some way to focus our evaluations and consequent developmental decisions to advance the women who would outperform otherwise-promoted men?

One thing that we could do is throw out potential ratings entirely, meaning you throw out the potential ratings and only promote based on the observed correlations between performance and promotions. In that case we did see a reduction in the gender gap in promotions. And that’s largely driven because, in this setting, female managers actually do perform better than men on observable sales performance metrics. And the performance ratings do reflect that.

But remember, the potential ratings are correlated with future performance within sex. So by throwing out potential ratings, you’d still be promoting worse managers because the people who got high performance ratings and high potential for both men and women turned out to be better managers than those who got the high performance and low potential. So you probably do want to promote those people who are also rated as high potential, it’s just that you have to level-set and check for bias across men and women.

So we don’t necessarily think that just throwing out the potential ratings is the best idea. It might achieve some equity, but also might lead to some mismatch and inefficiency as you promote people who wouldn’t make good managers.

Another alternative we explored would be to promote women as if their potential ratings were one point higher than they were rated. We found that this had a sharp effect on reducing the promotion gap. But at the same time, it would have the effect of not necessarily promoting the best managers.

The third thing we tried was to increase women’s potential rating by a point but only for the women who were high performers. This really affected promotion rates among women rated as high performance/low potential (in our case, they outnumbered men by a third in that one box).

It turned out that women who were rated as high performers/low potential who still got promoted turned out to be really great managers. So this seems like a good starting point where organizations can focus their efforts: Take a look particularly at women who are rated as high performers but low potential, and then target them for developmental opportunities.

Take a look particularly at women who are rated as high performers but low potential, and then target them for developmental opportunities.

I think sometimes organizations say that women in these categories might not apply for promotions and might not be interested in promotions. But I think once you give these developmental opportunities and once you make the possibility of a promotion more salient, then you may see more interest from women in applying for those positions. There’s this idea that we say in economics, “Aspirations are endogenous” meaning that your aspirations will be set lower if you don’t think that you can actually achieve them.

The importance of measurement

At Syndio, we encourage companies to run statistical tests to see if there are gender- or race-based differentials in employment outcomes like pay, performance ratings, and promotion rates. What are your thoughts on firms building this sort of analysis into their processes? Do you think transparent measurement is enough to achieve more equitable outcomes?

This is a really big question. First of all, measurement is a great first step. Think of a manager who’s rating, for example, five men and three women on performance and potential — and one woman receives a lower-than-average potential score. There’s just no way for an individual manager to look at their own data and see if it’s reflecting bias. Issues really only become clear at the highest levels of the organization (e.g. Nine Box ratings for tens of thousands people); for example, finding that women consistently get higher performance ratings but lower potential ratings than men. Organizations can then ask, “How can this be the case? If these employees are actually low potential, why is it that their performance is rated higher?”

I do think there are a lot of traps that you could fall into when you try to do a statistical analysis.

For example, for a pay gap you could say, “Well, we looked within our jobs/pay grades and we saw that there is no gap between the pay for men and the pay for women.” But suppose that your organization is failing to promote women. In that case, even within jobs, women will tend to have longer tenures because they’ve been stuck in those roles and they’re not getting promoted up. So by controlling for their job level, you’re missing that women just simply aren’t reaching those higher level jobs. If you’re going to say, run a regression where you control for job, you’ve really just taken off the table where the real bias lies and where we know that much of the pay gap is really explained by differences in promotion rates in particular.

You need to focus on whether the processes that you’re setting in order to promote people into those higher-level roles are fair — whether they are actually unbiased. If you do see a gap in the organization but not a gap within any individual job level or even a gap within any evaluation, it could just be that the evaluations themselves are biased or promotion rates into those higher paying jobs are biased.

Where organizations should start in addressing promotion bias

Suppose an organization suspects or finds that they have a significant gender-based difference in promotions, what concrete steps would you recommend that organization take to address this bias? Measurement is a good first step — then what?

The first place that I would start [if I used a Nine Box rating system] is asking: Is there a gap between the average performance rating and potential rating between men and women? And in particular, I’d look at that box of people who are rated as high performers but low potential and ask: Do I find women are much more likely to fall in that specific box compared to the other boxes?

And then after I looked at that high performer/low potential box, I would try to narrow down the scope of the problem and ask: If I gave certain developmental opportunities to the people in that box, could I see our organization actually advancing them? Because, at least in our setting and based on what we found, the people who fall in that high performer/low potential box actually turned out to have a lot of potential. And I think that concentrating efforts on providing more opportunities particularly to women and minorities who fall into that high performer/low potential box could be a very tangible place to start.

You mentioned earlier a little bit about this other research that you’ve done about the Peter Principle (i.e. great performers can be mediocre managers) where you risk this double-edged sword where you end up with less-than-great management and you lose a really star performer in that role. Can you share some key findings from that research? How might an HR practitioner use your research to make promotions at my company better at treating employees equitably and developing the right talent?

In our other research paper we were looking at data from hundreds of companies using a cloud-based sales performance management software where you could see tens of thousands of salespeople and their sales and everything that would go into setting their pay. When we were looking at those data, we found the single strongest predictor by far for whether someone was promoted was their sales performance.

The funny thing was that even as these salespeople with high performance got promoted, it was inversely correlated with their subordinates’ performance after they got promoted. I think this really goes back to this adage that I’ve heard a lot at the major professional conferences that the best salesperson doesn’t necessarily make the best sales manager — but we seem to promote them anyway. There is this idea of fairness, that you can’t not offer the promotion to the person who is the highest performer. But at the same time, a lot of the skills that make someone successful as a salesperson don’t necessarily translate into the skills that make someone successful as a sales manager.

Nine Box is really a way of distinguishing those high performers who really shouldn’t necessarily be promoted into management, which I think is one of the reasons it’s so ubiquitous as a ratings tool. Because this applies to more than just sales: the best engineer doesn’t make the best engineering manager or the best academic doesn’t necessarily make the best dean or the best university leader.

But in our promotions bias paper, we found that this widely-used solution to this conundrum also creates a major equity problem that is seemingly responsible for a lot of the gender pay gap, at least that we see in organizations.

There are things that organizations can do — for example, concentrating on women who are rated as high performers and low potential, checking for bias, and putting more effort into developing them into leadership roles. But this is definitely a story of how trying to solve one problem can create another.

Outcomes for women in the workplace

Coming full circle with today being Equal Pay Day, I would love your perspective on what the research shows about outcomes for women in the workplace. Are there workplace issues that you think rightfully get a good deal of attention right now? And ones that you think get more attention than they necessarily deserve?

Transparency in organizations is really an issue that has only recently gotten a lot of attention, but it’s certainly, I think, very well deserved. There has been a sustained, persistent earnings gaps for more than 50 years now since the 1963 Equal Pay Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It’s been a long time since we’ve had these laws that were supposed to make workplaces more equitable. And even though we’ve seen a lot of progress in terms of the occupations and professions that women are entering and labor force participation and education, we haven’t really seen the full catch-up, particularly with regard to how organizations are advancing women into the most senior leadership positions that pay the most.

One area where you could say the attention is misplaced is that organizations are often concerned that women aren’t applying for positions that are more senior. They post a position for a leadership role, either internally or externally, and they don’t get enough female applicants. Ingrid Haegele, who was a PhD candidate at Berkeley and who went to LMU Munich, was doing research with a large company and she found that women were less likely to apply internally for the first rung where you started to need to lead people. She complemented this with a survey of managers finding that women have a strong preference for not leading people, for not being in a position that would involve advising subordinates. And so organizations will say that their issue is entirely a supply-side problem. But I think that’s far too simplistic. Again, this goes back to that saying that “Aspirations are endogenous” [i.e. that a person’s inclination towards management or leadership roles is not innate but rather influenced by their experiences and socialization].

There’s evidence I discussed in our paper that men are more likely to complain — and they’re more likely to complain to women. There’s also considerations such as toxic work environments or the fact that many organizations frame leadership roles as being more agentic and masculine-typed, as opposed to being about building a team and fostering a collaborative culture. And organizations oftentimes, either when they’re advertising or they’re describing a position, use terms that stereotypically in people’s minds are more associated with men. And all of these factors can lead organizations to not develop women or provide them the experiences they would need in order to discover for themselves whether those leadership roles would be right for them.

So I think it’s overly simplistic to say that “The problem isn’t with ourselves, it’s with the pipeline.”Now there’s better research showing best practices for organizations to describe jobs in unbiased ways and provide developmental opportunities to actually prime the pipeline. And you have to get more creative than just where you advertise, for instance, or the traditional EEO requirements. It’s really about the culture of the organization and changing how people think about what it means to be a successful leader.

In my experience with business leaders, there’s this reflex that “It’s a recruitment problem. We’re just not getting the candidates that we want.” So I think that in the DE&I space we’ve over-indexed goal setting around recruitment. It’s easier to say “Just bring me super-qualified female candidates that look like leaders to me” rather than being asked to reframe how they develop and think about talent.

I try to teach this to my Masters of HR students all the time. You see so many versions of this problem! For example, we were talking about short-term incentives this week and about how organizations will reward based on quantity — and then the quality of the product suffers. I think the fundamental issue is that it’s just harder to measure the quality of one’s output versus just the quantity of the output. But that’s kind of where the discussion stops.

But really, you need to have the processes and the systems in place to track and measure the things that you care about. And sometimes you have to fix this other problem before you actually get to the better practices.

And so I guess, in the same way that you hear “We don’t get enough women applying for promotions”, well, you have to fix the upstream issue first. And there are a lot of things organizations can do to improve there. Because if you don’t, by the time that you’ve arrived at the decision of who to give a shot in a role, it’s just too late.

Any other closing thoughts?

I do think there’s good evidence for why we should be very deeply suspicious about Nine Box or the entire enterprise of just asking managers to rate their subordinates on potential and then taking them at face value. On one level, there’s role congruity theory, which has a well-established body of evidence that people rate women lower on leadership. You can give two of the exact same resumes with the exact same background, but the resume with the female name is consistently rated by recruiters and others as being less likely to be a good leader.

It’s also the case that when people are asked to give adjectives associated with men, adjectives associated with women, and adjectives associated with being a leader, the correspondence between the leadership adjectives and the male adjectives are very similar to each other — and much unlike the female adjectives. Or the fact that, even from a young age, when people are asked to draw a picture of a leader, people draw men. So I think, stereotypically there’s this association that men are going to make better leaders. But again, on objective metrics, that’s just unfounded.

There’s also an old boys’ club effect that men just have access to different forums for interacting with each other and people might give higher potential ratings to avoid conflict with those whom they have to interact with socially. Similar to the fact that men tend to complain more and so you might give them higher ratings because you don’t want to hear people complain to you. Also, we found that managers rate their male subordinates as being more likely to leave and more likely to quit. And these potential ratings, they are accurate: men in our setting were more likely to quit. So we think that managers may be giving men higher potential ratings almost as a carrot at the end of the stick in order to retain them.

All this to say, you can’t necessarily take it on face value that if you ask managers to rate this subordinate that they’re going to come back with unbiased answers. And they probably don’t know it! They might not be able to see the forest for the trees from their vantage point. This is why conducting analysis and looking at the data from a higher level should be done centrally. So that organizations can say, “Even if people down below don’t know there’s a problem, we can tell if there’s a problem .” And then they can start to think about the things that they can do to address it.

To close pay gaps, companies must analyze promotion equity

In an equitable world, Equal Pay Day would not need to exist at all. As we discuss solutions for making progress, it’s crucial to recognize that the pay gap is not just about unequal salaries but also about the lack of promotion equity. Alan Benson’s research sheds light on how promotion gaps contribute to pay gaps and highlights the need for companies to analyze their promotion practices to address this issue.

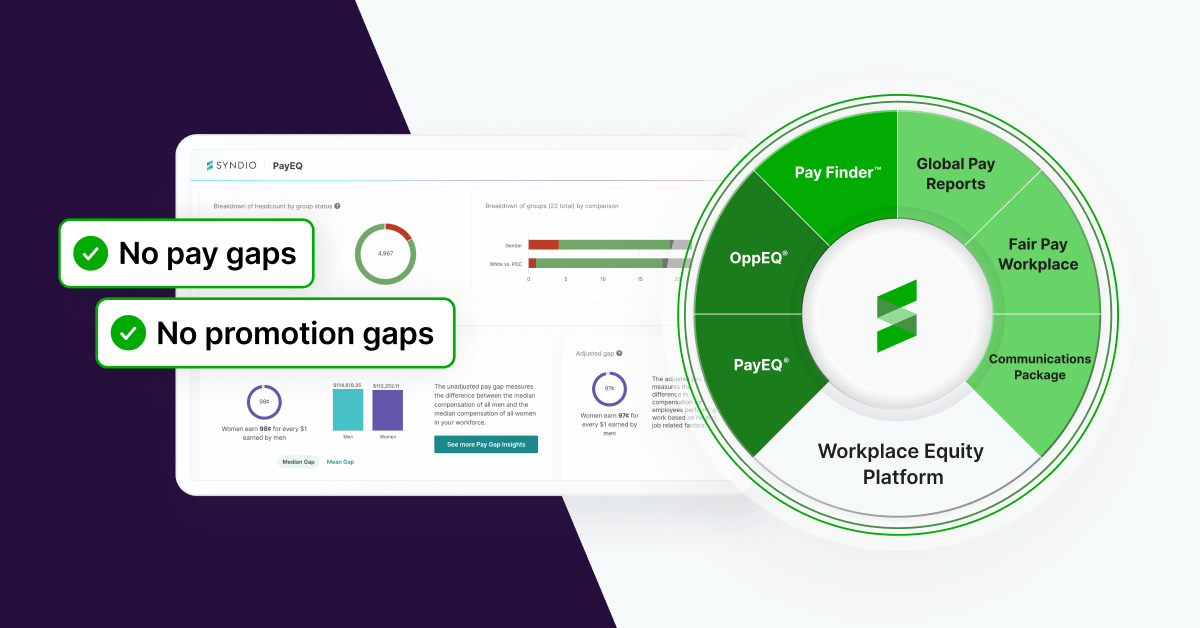

And doing so doesn’t have to be complicated. Syndio’s Workplace Equity Analytics Platform now offers a Promotions Analysis feature set in our OppEQ solution specifically designed to make it fast and easy to identify promotions disparities by gender, race, and intersectionality. By taking action towards ensuring promotion equity, organizations help build fair and equitable workplaces — and a future where Equal Pay Day is no longer needed because it’s January 1 for everyone.

Featured guest