As the entry point for joining your company, the recruitment and interview process has a huge impact on the overall state of workplace equity in your organization, not to mention that this process is the first impression of how your organization treats its people. Recruiting from a broad talent pool and diverse candidate sources, removing unnecessary requirements or weak proxies for job requirements and biased language from job descriptions, and offering equitable starting pay are all key components of a fair hiring process.

However, early conversations with candidates about compensation can unintentionally lead to problematic results — and setting the wrong starting pay will only exacerbate pay gaps within your organization. In fact, some research points to problematic differences in starting pay as accounting for a large percentage of pay gap issues in organizations today. Two historically common practices that can contribute to inequity during salary negotiations are asking for salary history and asking for salary expectations.

Since Massachusetts became the first state to prohibit employers from asking about salary history in 2016, 20 other states and 21 local jurisdictions have passed laws with varying levels of bans against requesting salary history and/or using salary history to set starting pay. However, asking for salary history is still legal in most states (and in fact, two states — Michigan and Wisconsin — have banned salary history bans). Additionally, using past salary to explain salary differentials is not a valid defense in a pay equity case. In Europe, the proposed EU Directive on Equal Pay and Pay Transparency includes a provision banning employers from inquiring about salary history.

A commonly suggested workaround to avoid asking about salary history is to switch to asking candidates what they “expect” to make. This tactic comes loaded with potential for inequity — and somewhat surprisingly, can often have worse outcomes than asking for salary history!

Below we share insights into the effect of asking candidates about their salary history or salary expectations, as well as recommendations for discussing compensation with prospects in a way that does not introduce bias.

What happens when organizations ask applicants about salary history or salary expectations?

Broadly speaking, bringing salary history and/or salary expectations into the compensation conversation perpetuates cycles of pay discrimination that will set back any efforts an organization may be making to close their pay gaps.

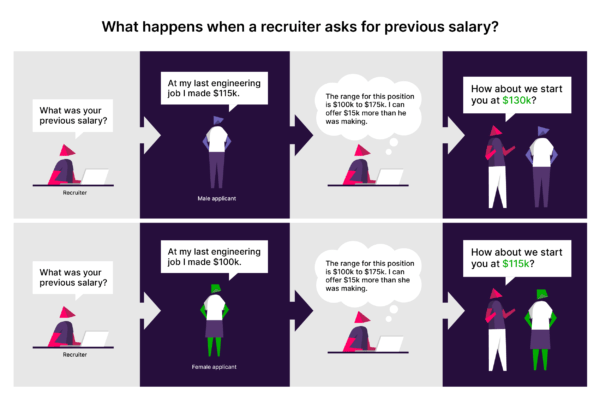

To illustrate this point, let’s start by examining the likely effects of asking for salary history. The examples below are based on gender, comparing male engineering applicants to female engineering applicants. We use gender here for ease of illustration, but these concepts apply to comparisons by race and ethnicity, or other protected categories of employee identity.

Let’s start with the fact that there is existing gender-based discrimination in the labor market: on average, female engineers make about 13% less than male engineers with comparable skills and relevant experience. Black and Hispanic engineers make about 16% less than white engineers with comparable skills and relevant experience. Remember that applicants to your organization worked in this labor market — so your applicants’ work histories likely reflect these disparities. That is to say that even if your organization pays people equitably, your applicants came from a world in which they were likely paid differently based (in part) on their gender, race, or other protected category.

Example 1: The problem with asking for salary history

In our stylized example, the male candidate represents an average male worker and the female candidate represents an average female worker. When the recruiter asks for each candidate’s previous salary, the male applicant replies, “I made $115,000 at my last job as an engineer” and the female applicant replies, “I made $100,000 at my last job as an engineer.” If the internal range for the job position is $100,000 – $175,000 and the recruiter wants to offer each candidate $15,000 more than they were making at their previous job, then they would offer a starting salary of $130,000 to the male candidate and $115,000 to the female candidate.

Even though the recruiter is trying to be fair by offering each candidate $15,000 more than they are currently making, the recruiter is actually “importing” any inequities that may already exist in the female engineer’s salary history, starting from her very first job. Stanford researchers found that entry-level salaries in STEM are more than $4,000 higher for men than what’s paid to women with comparable credentials, meaning that the gender pay gap in STEM begins right out of college. Asking for previous salaries may essentially kick the proverbial pay equity liability “can” down the road since the hiring company risks inheriting unlawful pay disparities from a candidate’s previous company.

Entry-level salaries in STEM are more than $4,000 higher for men than what’s paid to women with comparable credentials.

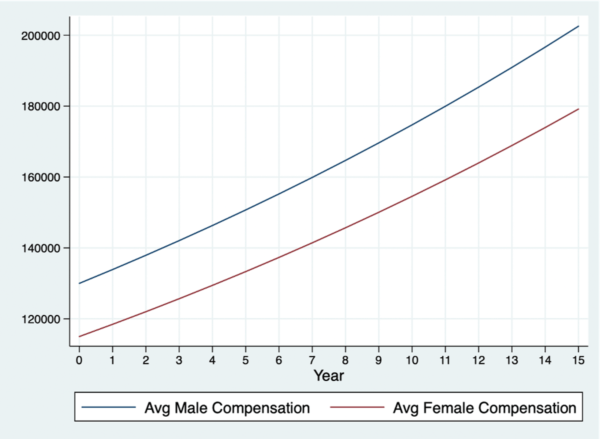

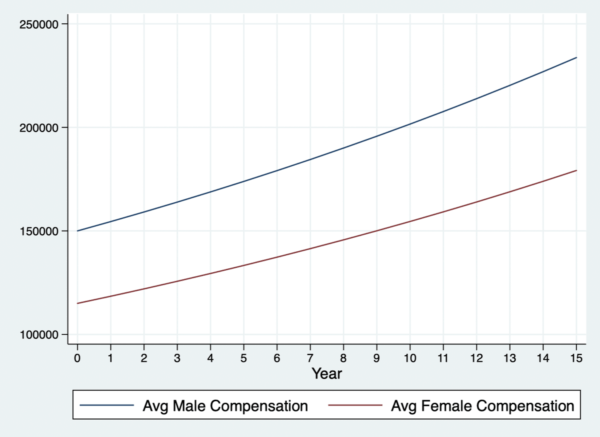

Pay inequities brought in at the time of hire will only compound over time if not addressed. The graph below shows how much better off the male engineer would be than female engineer over a 15-year period assuming that both get the same 3% raise every year — that’s a total difference of $279,000.

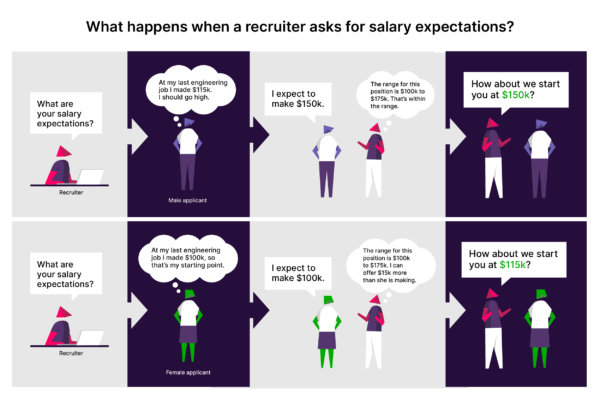

Example 2: The problem with asking for salary expectations

Research suggests that men are more likely than women to feel comfortable when asking for more in negotiation settings. Studies also show that men initiate salary negotiations about four times more often than women — and when women do negotiate, they typically ask for and receive 30% less. This “confidence gap” predicts differences in what female applicants are likely to ask for when prompted with inquiries about salary expectations. This matters because of the importance of anchoring bias in negotiations — that is, the first number brought up in tends to set the boundaries and narrow the possibilities for further negotiation. Because of the heavy weight given to the first number placed on the bargaining table, the higher the initial starting number, the higher the final number will likely be and vice versa.

Research also shows that women are socialized to negotiate differently than men — and can even get penalized as being seen as less hirable and less likable if they negotiate more aggressively. One study on gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations found that, “When hiring candidates, evaluators are significantly less willing to hire both men and women who initiated negotiations. However, the negative effect of negotiating is more than two times greater for women than it is for men. When assessing willingness to work with candidates, there was no decline in evaluators’ willingness to work with a male candidate who attempted negotiations. However, the negative effect of initiating a negotiation is 5.5 times greater if the candidate is female.”

When assessing willingness to work with candidates… the negative effect of initiating a negotiation is 5.5 times greater if the candidate is female.

In our example, if the recruiter asks for salary expectations rather than salary history, the male applicant may think to himself, “Well, I made $115,000 at my last job as an engineer. I should lead with a strong number.” He then tells the recruiter, “I expect to make around $150,000.” In comparison, the female applicant may think to herself “Well, I make $100,000 at my current job as an engineer, so that’s my starting point.” She says, “I expect to make around $100,000.” (Based on the empirical research noted above, these are reasonable representations of the average male and average female responses to this prompt).

If the range for the job position is set for $100,000 – $175,000, then the recruiter may feel comfortable offering the male applicant what he asked for since it’s well within range: $150,000 starting salary. Meanwhile, to be competitive and offer the female candidate more than she expected, the recruiter offers her $115,000.

As in Example 1, any starting pay inequities will only compound over time. The graph below shows how much better off the male engineer will be than the female engineer over a 15-year period assuming that both get the same 3% raise every year — a total difference of $651,000. Studies suggest that women stand to lose $500,000 to more than $1 million throughout their career due to not negotiating their starting salary or subsequent salary increases.

Women stand to lose $500,000 to more than $1 million throughout their career due to not negotiating their starting salary or subsequent salary increases.

Why asking for salary expectations can sometimes be worse than asking for previous salary

In our example, the average female engineer/job candidate would actually be better off if the recruiter had anchored starting pay based on previous compensation, rather than compelling the applicants to negotiate blindly and declare their expectations. Over 15 years, assuming both got the same 3% raise every year, the male engineer in our example out-earns the female engineer by over twice as much when asked about salary expectations compared to salary history.

How to have an equitable conversation about salary

So, how can recruiters and hiring managers discuss compensation fairly, without relying on candidates to provide their salary history or salary expectations?

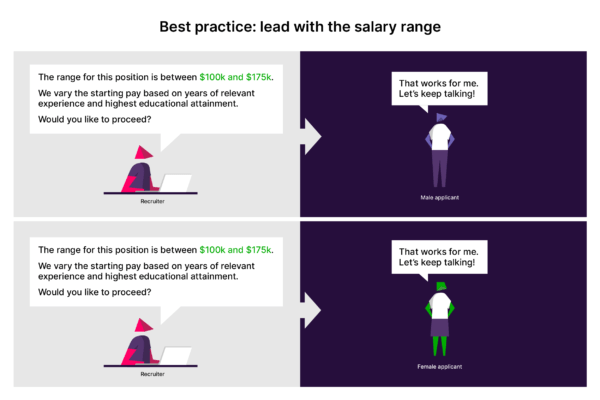

First and foremost, recruiters should be equipped with salary ranges (potentially based on hypothetical candidate profiles) that they can present to candidates at the start of the application or interview process. With these predetermined ranges, recruiters can consistently start the conversation the same way with every candidate by putting the first numbers (i.e. the salary range) on the table.

In our examples above, the recruiter should tell both candidates up front, “The range for this position is between $100k and $175k. We vary the starting pay based on years of relevant experience and highest educational attainment. Would you like to proceed with the interview process?” This lets the applicant know whether the earning potential works for them — and naturally leads to a conversation regarding their experience and qualifications.

That conversation around meaningful, measurable, and job-related differences should determine where new employees’ salaries fall in the range — not differences in their current earnings, or even more nebulous (and potentially biased) differences in what they “expect” to be paid.

How to set the right salary ranges

The 2023 Workplace Equity Trends Report found that 24% of organizations are concerned about “defining the right ranges” in preparation for new pay transparency laws. However, determining your salary ranges doesn’t have to be daunting. Syndio’s PayEQ Pay Finder™ uses candidate characteristics (or potential characteristics, such as those in your job posting) to create a salary range that is both internally equitable and externally competitive.

Create a salary range that is both internally equitable and externally competitive.

Remember that applicants have access to the Internet — and workers are democratizing salary information in Google spreadsheets, LinkedIn, Reddit threads, and even on TikTok. For larger organizations, there may be additional information posted about your hiring practices. Since employers often cannot control this information and it may not be accurate, being transparent about your real ranges avoids communication pitfalls.

Posting salary ranges is only going to become more common, not only as a way to improve equity in the hiring process, but also to future-proof against expanding pay transparency legislation. One in three workers in the U.S. are subject to laws requiring some form of pay transparency now or in the near future. Companies that adopt a nationwide approach to salary range transparency will simplify compensation administration compared to companies taking a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction approach. Leading companies are already reacting to the writing on the wall — for example, Microsoft has announced that, starting no later than January 2023, they will post salary ranges for all job openings.

Improving equity from day one

It can be tempting for recruiters and hiring managers to lean on salary history (where legal) or salary expectations as a shortcut in salary conversations. But any cost savings or time advantage felt by recruiters is not worth it when pay inequities have to be remediated later on in the employment lifecycle. Additionally, placing the burden on applicants to guess at fair compensation inside an information vacuum is a recipe for a poor employee experience. When job candidates don’t know what the real range and budget is for the role to which they are applying, new hires may walk away thinking that they could have asked for more and feeling that they may be underpaid as a result of their negotiation.

In contrast, proactively posting job salary ranges can actually streamline recruiting because applicants know upfront whether a listing is within the range that they are looking for — weeding out candidates who would be expecting more before they waste their time on applying (and your recruiters waste time reviewing their applications).

Not asking for salary history can even possibly lead to a more diverse recruitment process: a 2019 study found that companies that did not have access to salary history information broadened their pool of applicants, evaluated more applicants, and asked more questions of candidates. Additionally, this LinkedIn article shares that, “In states where salary history bans have been enacted, pay for those who switched jobs increased, on average, 5% to 6% more than for those who changed jobs in other states. But the boost was even larger for African Americans, who received increases that were 13% to 16% higher, and for women, who received bumps that were 8% to 9% higher.”

To build a truly equitable workplace, companies must ensure that employees are being treated equitably at every stage of the employment lifecycle — including the moments before a job candidate is ever hired. Taking salary history and salary expectations out of the interview equation are two steps that can help create a more equitable interview and hiring process for every worker.

Want to learn more about how your company can quickly establish internally equitable and externally competitive salary ranges?

The information provided herein does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice. All information, content, and materials are provided for general informational purposes only. The links to third-party or government websites are offered for the convenience of the reader; Syndio is not responsible for the contents on linked pages.