The pandemic revealed some cracks in our society, and one of the largest is the lack of support for employee caregivers.

Approximately 18 to 22% of U.S. workers provide care for an elderly, sick, or disabled family member. One in three workers have children under 18, and of these, a quarter have children younger than six years old. 70% of working caregivers suffer work-related difficulties due to the demands of dual roles, and during the pandemic 33% of caregivers reported they had permanently lost or reduced their source of work income due to their caregiving responsibilities.

Workers left their jobs because they were unable to find affordable paid help, unable to find high-quality help, and not able to meet work demands because of increased caregiving responsibilities.

Yet it wasn’t until very recently that some employers began tracking and analyzing caregivers as an employee identity group. Syndio’s 2023 Workplace Equity Trends Report revealed that 12% of organizations now track caregiving status as an emerging identity group. Read on to learn more about the relationship between employee caregivers and workplace equity.

Women, particularly women of color, are most impacted

This is an issue that significantly impacts women: Two out of every three caregivers in the U.S. are women. During the pandemic, nearly 3 million women left their jobs, to a large extent due to caregiving demands that arose when schools and childcare options closed. 53 million informal caregivers provide care to someone who is ill, disabled or aged in the U.S., and long Covid cases, a number now estimated to be over 450,000, will add to that number. Black and Latina women left the labor force at higher rates than any other group, primarily due to their caregiving responsibilities.

A recent McKinsey & Company study indicated that during the pandemic, 1 in 4 women considered leaving their job in the public sphere or downshifting their careers, compared to 1 in 5 men. The numbers were higher for working mothers, women in senior management positions, and Black women.

By January 2022, men had fully regained all the jobs they’d lost due to the pandemic, but the same cannot be said for women. As of September 2022, the labor participation rate for adult women was around 58%, barely higher than the 57% it was in January 2021, which was a 33-year low. For those women who remained in the workforce, a July 2022 survey by Great Place to Work showed that dissatisfaction with the workplace is high: 54% said they’re open to finding a new job in the next six months. One in 10 said they’d like to leave their job, but are not able to do so.

It’s easy to see why employee caregivers are forced to drop out of the workforce. Studies have shown that for employed caregivers, the hours are similar to having a demanding part-time job in addition to a paying job. Caregiving roles and responsibilities sometimes last for years, and involvement can be either ongoing or sporadic.

Women have long been more often responsible for family caregiving and housework, but the imbalance is especially stark between men and women in leadership roles. Women in entry-level positions are about twice as likely as men to be handling all of that work, but the gap nearly doubles among leadership employees.

The toll on productivity and performance

For caregivers who try to remain employed, the toll on their productivity and performance is heavy: A study published by Harvard Business School found that 53% said they had to start work late or leave work early, 15% reduced their work hours, and 14% took a leave of absence. Additionally, a group of 8% had received a warning about work performance or attendance.

A September 2022 survey of employee caregivers by three caregiver organizations showed that 32% said “time away from work” was their biggest challenge with caregiving. 80% of caregiver employees in the Harvard study said they felt that their caregiving had affected their productivity, preventing them from performing at their highest levels.

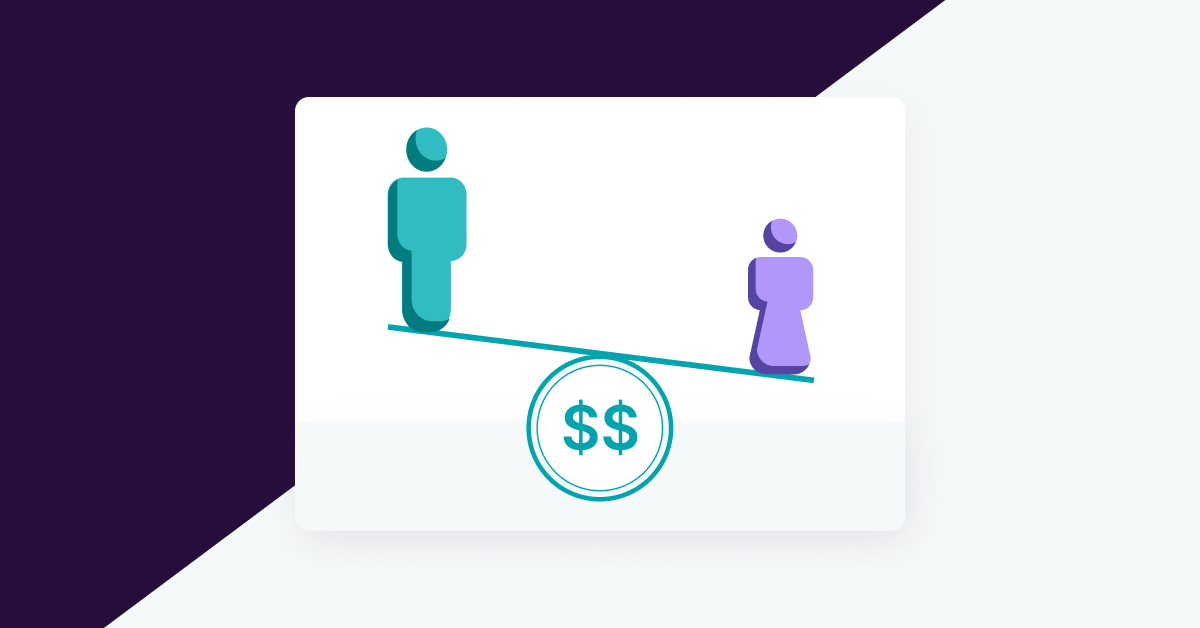

Caregiving poses a financial sacrifice for women in particular, long term as well as short term. Employee caregivers often lose income, savings, and benefits that would provide financial security in retirement. Being forced to quit jobs, shift from full- to part-time work, or decline promotions that would not offer the flexibility to provide care at home can all undermine long-term financial well-being. The most common example of this is the “moms’ wage gap”: Moms working full-time earn just 74 cents for every dollar paid to a dad in the U.S., the National Women’s Law Center reports — and for many moms of color, the pay gap is even larger.

The resulting economic cost is high for the nation as well: The U.S. gross domestic product would jump an extra $1.7 trillion by 2030, or 5.5% over current projections, if employers and governments put more support in place for working caregivers, according to an AARP report.

Employers also face a liability risk. Multiple regulations offer employed caregivers some protections, and a 2016 study found that the volume of litigation increased dramatically in the past 10 years compared to the prior decade. While most were complaints related to pregnancy or maternity leave, nearly a third were about caregiving: 11% involved elder care, 9% involved care for sick children, 6% for care of a sick spouse, and 5% for care of a person with a disability.

Demands on employee caregivers contribute heavily to the opportunity gap

One national retail chain discovered the impact of caregivers on its business when the HR team dug deeper into their pay equity analysis to uncover what was causing their median pay gap.

Working with Syndio’s experts, the team found that while representation in leadership and high-paying functions was on track at headquarters, employees at the company’s retail stores weren’t advancing equally. Women were well represented as assistant store managers at 53%, but were not moving up to store manager; only 34% of managers were female. Additional research showed that this shortfall was largely among women of color, whose representation in the store manager level was less than half of what it was at the assistant store manager level.

After analyzing the data and interviewing employees, the company isolated the root cause of the problem: Women of color were more adversely impacted by the pandemic than other groups of employees. Due to their caregiving responsibilities at home, the hours and flexibility required for a manager position weren’t feasible.

By identifying the inequity by group, job, and location, the retailer was able to address the issue and put a plan in place, which included restructuring job requirements to ensure there was more opportunity for women of color to advance. This change moved the needle on their leadership diversity and pay gap goals.

What should companies do?

The first step is to collect this data so you can track promotions, retention, and pay equity for employee caregivers as a group, then analyze it for any inequities. Another piece of the puzzle is to audit your job responsibilities to see if there are unnecessary barriers for people who may need the scheduling flexibility required for caregiving.

It’s important to work with caregivers in your organization to ensure benefits, flexibility, and treatment accurately reflect employees’ needs. Your organization could consider several benefits that caregiver support groups recommend that employers offer to their caregiver employees, including:

- Provide an employee caregiving interest group, representing a diverse range of caregiver employees, to serve as a resource to management and other employees

- Train managers on the issues and providing adequate back-up to help them interact effectively with caregivers

- Offer flexible work, including options such as compressed workweeks, part-time hours, and work-from-home options

- Provide referral services such as external coaches or agencies that can save hours spent searching for appropriate paid caregivers

- Include subsidies for childcare in your benefit package

- Offer emergency backup childcare and/or backup care subsidies to help caregiver employees fill temporary gaps in regular arrangements, which can be expensive and difficult to source

- Negotiate discounts on behalf of your employees with local childcare centers

- Offer flexible spending accounts including dependent care so employees can pay for dependent care with pre-tax dollars

- Provide substantial paid leave for caregiving responsibilities, in addition to paid vacation and sick time

In a 2021 survey, 84% of employee caregivers said that they’d be interested in benefits from their employer that provided resources, guidance, or caregiving support. At a time when organizations are seeking ways to recruit and retain top employees, providing caregiver support can be a differentiator.

The challenge of supporting employee caregivers is not going away. The U.S. is faced with an increasingly aging, chronically ill, and disabled population, just as many other industrialized nations are. At the same time, many families are unable to find affordable, high-quality caregiving options such as a facility or in-home help.

The need for tracking caregiving as an employee identity is clear; the challenge this need represents is both a threat and an opportunity.

Learn more about the current trends in employee identity tracking and workplace equity in our latest Workplace Equity Trends Report.