Organizations want to reward high-performing employees, and often tout a “pay for performance” philosophy in which more capable employees would theoretically earn more than less experienced, less talented, or less hard-working employees performing similar work.

However, in practice as we help hundreds of organizations analyze their pay data in the Syndio Workplace Equity Analytics Platform, we more commonly see weak or zero relationships between pay and performance — and that performance tends to explain a relatively small amount of the variance in employees’ compensation. This means that many organizations aren’t actually rewarding what they intend to reward, or at least not to the degree they imagine.

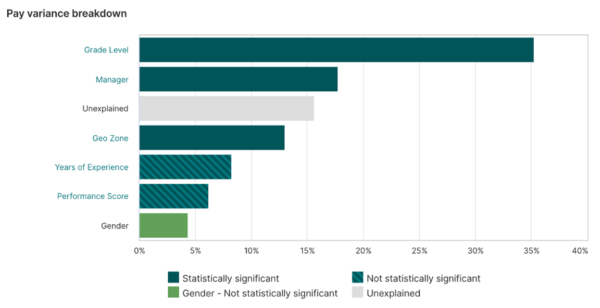

Below is an example screenshot from the Pay Policy Analytics page from PayEQ™, our pay equity analysis software. Here we see a common case, where performance scores do not have a statistically significant impact on pay, and explain a relatively small amount of the total variance in pay.

In this post, we’ll explore why this is frequently the case, and how compensation programs can rethink the role that performance plays in total rewards to ensure that they effectively reward the traits and behaviors that drive better business outcomes.

What does a common “pay for performance” plan look like?

Pay ranges are developed using benchmark jobs, that is, jobs that have been matched to compensation survey data. Jobs are frequently assigned to these pay ranges based on factors such as the skills required, responsibilities in the role, working conditions, or market pay rates for similar roles. Since these are ranges, some people within the role will earn more while others earn less. The midpoint of the range typically represents what is considered the competitive market rate for the jobs in the range.

A key concept here is the “compa-ratio” (short for compensation ratio), which describes an individual’s position within their job range, in which their compensation is represented as a ratio of the range midpoint. For example, a compa-ratio of 0.8 means the individual’s pay is 20% below the pay range midpoint, whereas a compa-ratio of 1.2 means pay is 20% above the midpoint.

In a pay for performance plan, an employee’s compa-ratio should ideally reflect their performance in their role. Conceptually, this often takes two forms that can be at odds with each other:

- Tying the compa-ratio ranges to suggested measures of competency (e.g., compa-ratios between .8-.9 still have gaps in competencies and are learning in their roles, 9-1.1 are proficient, and those above 1.1 are highly proficient, should be able to mentor others, and may be ready for promotion into another role).

- Tying merit increases (the pay raise process that happens once or twice a year) to a combination of an individual employee’s performance review and their placement in the range (e.g., employees that are lower in the range receive higher increases for the same performance rating than employees who are higher in the range).

Why do so many programs fail to actually pay for performance?

Reason 1: The marginal impact of performance on pay tends to be small relative to the overall variance in compensation.

Typically, managers are allocating a limited merit increase budget (historically around 3% of total base payroll) between their employees, so budgeted dollars shift from employees with low performance scores to those with high performance scores. A performance plan might have high performers garnering 5-6% raises, employees meeting expectations getting the budgeted 3%, and those who fail to meet expectations receiving 0-1% increases.

However, differences in merit increases based on performance are small relative to the variance in employees’ compa-ratio to begin with. It could take years for an employee who consistently outperforms a peer to catch up in terms of base pay, if the peer started with a higher compa-ratio. Employees’ compa-ratios can vary significantly depending on the level of governance around pay decisions at the time of hire, when an employee was transferred or promoted, or any other time when an employee’s job was assigned to the range.

Additionally, these differences are small relative to changes in the pay rate of the market. For example, we often see compression related to tenure, where long-tenured employees tend to earn the same amount or less than their peers, particularly in higher earning roles.

Reason 2: Performance is both about skills and discretionary effort. Organizations struggle to track or measure skills, and discretionary effort can vary from year to year.

Performance is a combination of multiple factors — an employee’s innate talent and abilities, their skills and knowledge, and the work they’re actually putting in (their “discretionary effort”). Skills and knowledge can be gained, and they are durable. An employee doesn’t gain relevant experience and then lose it the next year!

Discretionary effort is related to the recent buzz-word “quiet quitting”, where employees show up to a job and collect their paycheck, but are doing the bare minimum of what’s expected of them. These “quiet quitters” are choosing not to put discretionary effort into their work — potentially because they perceive that such effort is not rewarded.

A pay for performance plan would, ideally, provide financial incentives for all employees to gain new, relevant skills and knowledge, and to put in the work to get their jobs done well. However, the relationship between skills/knowledge and compensation is weak and inconsistent as organizations for years have struggled to identify and track their employees’ skillsets. The most obvious incentive to gain new skills is because it enables you to get a new position.

The relationship between discretionary effort and compensation is also tricky, as base pay tends to be “downward sticky”, meaning employers rarely reduce salaries. That said, discretionary effort is not that way! Google is currently trying to curb tenured employees’ tendency to “rest and vest”, where they continue collecting their salary and watc their stock options vest while no longer putting in the same level of effort as they previously had.

So, let’s compare these things we want to encourage (building relevant skills and knowledge for a role, and employees putting in work to fulfill that role) to the process we have in place (small incremental increases relative to peers who may already be earning more). This may create the desire to “hustle” for employees who are new in a role or early in their career, but it doesn’t create a system that sufficiently differentiates pay based on performance, or one that creates a lasting incentive for employees to do their best work.

Reason 3: Your performance evaluation process may need a lot of work.

Performance reviews can be biased in a variety of ways that make them less accurate and in ways that may potentially harm workplace equity. Employees often complain that performance reviews do not provide meaningful feedback and goals. When done well, performance reviews require a significant amount of time from multiple stakeholders.

If you do tie compensation to performance reviews, then your compensation program is only as good as your performance management program.

You should not discount this threat of a potential downstream impact from a biased process as you tie more employment processes together. It is a mistake to have them all operate in silos, but creating relationships between them requires both good program design on the front end and a real-time analysis of results to ensure you are achieving the desired outcome.

What should you do about it?

- First, define what you believe should determine base pay, leaving the “discretionary effort” piece aside. What specific characteristics about employees should determine their salaries? How much should another year of relevant experience be worth? What pay premium would you like to provide for key skills, and what are those skills?

- Compare your actual pay outcomes to your current policies. In our compensation analytics software PayEQ®, we use the Pay Policy Analytics feature to evaluate actual outcomes vs. stated policies, allowing organizations to take stock on how their programs compare.

- Come up with a transition plan to align pay for current employees with the intentions of your pay program design. This process will likely take time and budget, but provides an opportunity to reinforce to your employees that you value them and want to treat them fairly. As pay becomes more transparent, this will go a long way to building “pay explainability” into your compensation program.

- Use innovative ways to make sure your organization follows pay program guidelines for all pay decisions: new hires, promotions, transfers, or pay adjustments for people who gain new skills or experiences that they did not have before. We developed Pay Finder™ specifically to enable companies to make fair and consistent pay decisions throughout their organizations. Compensation teams can be virtually present for every pay decision made by recruiters and hiring managers.

- Finally, consider using variable pay instead of base pay as the lever that can incentivize effort from employees, year in and year out. While the acquisition of new skills and knowledge should be rewarded through salary, short-term incentives and recognition can directly reward effort and specific behaviors. For this to work, it is critical that the performance review process is designed well and reflects goals that meaningfully motivate employees and remain relevant throughout the year (or change as priorities shift).

Clarity builds trust

Being clear about how performance is defined and rewarded is critical in keeping your employees engaged, managing their expectations, and engendering their trust. A report from i4pc found that “Productivity is significantly affected by how much (or how little) trust exists within the culture of an organization.” Employees want to understand why they’re paid what they’re paid and to believe that they are paid fairly in relation to their peers. Gartner found that only 38% of employees “report that they understand how their pay is determined” — but when organizations educate employees about how pay is determined, employee trust in the organization increases by 10% and pay equity perceptions increase by 11%.

Talk to our team to learn how Syndio’s Workplace Equity Analytics Platform can help you ensure that you are paying for what you intend to pay for and that your pay is equitable for every employee.

The information provided herein does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice. All information, content, and materials are provided for general informational purposes only. The links to third-party or government websites are offered for the convenience of the reader; Syndio is not responsible for the contents on linked pages.