Today is U.S. Equal Pay Day — which measures how far into 2024 the typical woman must work before they earn as much as men earned in 2023. The date is based on the median pay gap, which is a blunt instrument measuring how women can expect worse outcomes in the labor market when it comes to wages. But why is there a gender pay gap?

My colleague Zev Eigen has previously written about the drivers of the pay gap. Below we share new research, which combines government data, economic research, and anonymized data from over 100 Syndio customers, to break down the overall gender pay gap into parts that help us understand why women consistently earn less than men — and what organizations can do about it.

How big is the pay gap in 2024?

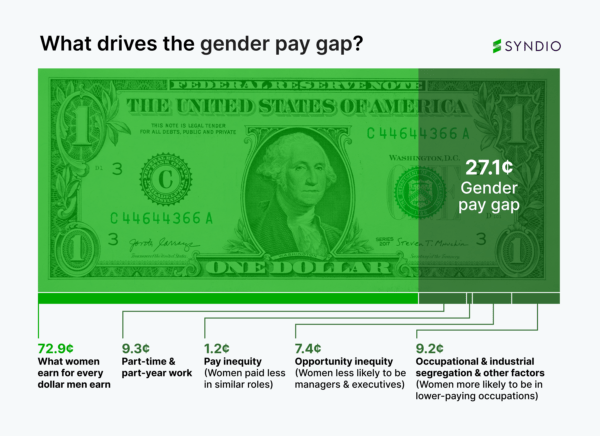

Currently, the gender pay gap for all U.S. workers stands at 73 cents. As we discuss below, a portion of this pay gap is driven by differences in the rates at which men and women work part-time or part-year. Other common measures exclude part-time or part-year workers, typically reducing the gender pay gap. The U.S. gender pay gap using this measure is 82 cents. As you can see, there is some variation in the pay gap based on who you include or exclude, how earnings are measured in different surveys, and how you calculate the pay gap.

The most common calculations are the median pay gap (measured as the difference in earnings of the median or middle-earning worker for each gender) and the mean pay gap (measured as the difference in average earnings). Mean pay gaps tend to be larger due to the combination of two factors: the people who earn the most tend to earn a lot more than the typical worker, and those people are also more likely to be men.

The purpose of this research is to “deconstruct” the median gender pay gap, meaning break it into constituent parts and determine what proportion of the pay gap each part contributes. For each contributing factor, we will discuss our approach for measuring how much it contributes and what role organizations play in perpetuating or disrupting a specific factor.

1. Differences in part-time and part-year work

Bottom line: Gender-based differences in part-time and part-year work contribute 9.3 cents to the pay gap.

How we calculated this: We compared the same statistic across two datasets from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. We can calculate the difference in median earnings in the past 12 months for all workers, and then calculate it again when the data are restricted to full-time, full-year workers. The result is a significant reduction in the pay gap.

What can organizations do? An employee’s decision to work part-time or part-year is frequently driven by factors outside of an employer’s influence, such as competing responsibilities like study or caregiving. That said, flexible work and leave policies can keep employees from quitting entirely in response to demanding circumstances outside of work, and structured return-to-work programs can help employees re-enter the workforce after a break.

2. Pay inequity

Bottom line: Pay inequity — women earning less than male peers performing similar work — contributes 1.2 cents to the pay gap.

How we calculated this: To determine the portion of the pay gap that is due to gender-based differences that cannot be explained by neutral, job-related factors, we turn to Syndio’s database of pay equity analyses. For this analysis, we reviewed the pay equity analyses of 124 organizations covering over 2.8 million employees. Customers use Syndio’s PayEQ® to group employees in similar roles and apply multilinear regression to determine if there is a statistically significant gender-based difference in pay after accounting for other explanatory factors.

The average pay gap across all job groups in our dataset is 8.6%. This is comparable to estimates from economists Francine Blau & Lawrence Kahn, who apply various statistical controls (such as industry, occupation, and education) and find an 8% gender pay gap that is not explained by those factors. In our dataset, we find that other variables at the job-group level (most commonly tenure, job level, and location) reduce the observed pay gap to 1.2% across the 7,091 job groups analyzed.

What can organizations do? In the U.S., gender and race-based pay discrepancies are unlawful. It is an established best practice to conduct regular pay equity audits, analyzing groups of similarly situated employees for gender and race-based differences in pay. Over time, these practices have likely reduced gender-based pay discrepancies that cannot be explained by neutral, job-related factors.

In case studies with Syndio customers, we consistently find that roughly 90% of new pay equity issues are created when employees enter new positions through hiring and promotions, rather than through the annual merit increase processes. As such, organizations should provide clear, consistent guidance for how pay is set when individuals are hired or promoted. While manager discretion is frequently appropriate (some candidates’ experiences or skills certainly justify a pay premium), there is a real need for companies to apply greater consistency when these pay decisions are made.

3. Opportunity inequity

Bottom line: Opportunity inequity — women failing to advance into senior, management, and leadership positions at proportionate rates to men — contributes 7.4 cents to the gender pay gap.

How we calculated this: We restricted our database of pay equity analyses to those that only applied a job level hierarchy (including pay grade) as a control in their pay equity analysis. This lowered our sample size to 125 job groups from 14 employers analyzing roughly 32,000 employees. In these groups, controlling for level reduced the observed gender pay gap by 7.4 percentage points at the median.

Part of this gap is because women are less likely to make it into management positions, and part also represents women remaining at lower levels within a career track — both among managers and non-managers. In our U.S. Opportunity Gap research, we found that in aggregate EEO-1 data, women are 48% of all workers but only 40% of managers.

Combining this with the most recent earnings data from the Census Bureau broken out by EEO job groups, we find that 2.4 percentage points of the pay gap are due to this under-representation of women among managers. This assumes women managers earn as much as male managers, but the reality is that female managers earn 31% less than male managers, which reflects both occupational segregation (women tend to be different types of managers with lower pay on average) and job level (women are less likely to advance to higher-level manager positions, like director and VP).

What companies can do about it: The root cause of the opportunity gap is that women — and women of color in particular — are not advancing to management and leadership positions. Ultimately, these representation gaps are due to some combination of women failing to be hired, promoted, or retained in managerial positions — there have been long-standing inequities in the flows in, up, and out.

Organization should begin with a representation audit, identifying where and to what degree particular communities representation begins to fall. The next step is identifying which flows are driving those issues — hiring, promotion, retention — and potential leading indicators or root causes, such as differences in performance ratings or job expectations — both explicit or implied — that may cause certain communities to think these roles are not “for them.” Syndio’s OppEQ® solution helps organizations conduct these audits, identify drivers such as promotion gaps, and set meaningful representation goals.

With this deeper level of insight, your organization can set meaningful goals, track the right metrics, and design the right programs to close opportunity gaps.

4. Occupational and industrial segregation, plus other causes

Bottom line: Women working in different jobs or different industries from men contributes 9.2 cents to the pay gap.

How we calculated this:This calculation represents the residual pay gap — meaning the part of the pay gap that is not explained by part-time or part-year work, pay equity, or opportunity equity. Blau and Kahn estimated that occupational and industrial segregation represent approximately 50% of the wage gap, which is approximately the same as the portion here when we discount part-year and part-time work. Other factors may include those accounted for during a pay equity analysis, such as differences in tenure or skills.

What companies can do: On some level, companies are beholden to the labor market availability of talent. That said, they can still influence and reduce the amount of gender segregation over time by ensuring they support women throughout all stages of the employee lifecycle. For example, the share of women graduates in engineering is higher than the share of women among engineers, partially because women are more likely to leave engineering as a field — often referred to as the “leaky bucket” problem.

Organizations can directly influence this by identifying if and for what departments or positions this is occurring at their organization, and updating policies or developing programs that can address it. It could be an openly hostile or cutthroat working environment, or a lack of supportive programs that could help women stay on as they progress through their careers and lives. For example, research has found that having children can have opposite impacts on men and women’s career prospects, from labor force participation to earnings growth.

These drivers are not root causes of the pay gap

One challenge of this research is that drivers of these pay gap components are frequently overlapping. For example, differences in when and how women negotiate as compared to men — and how that negotiation is received — can drive both pay equity and opportunity equity issues.

What academics call “role congruity theory” (where individuals have a gendered understanding of certain professions, such as imagining a male when they picture an engineer) drive both opportunity inequity and occupational segregation. Responsibilities for caretaking which disproportionately fall on women can lead women to seek out part-time work, take more career breaks, or seek more flexibility in their positions — all of which contribute to the underlying pay gap drivers we detailed above.

How companies can tackle their pay gaps

There are two instruments companies frequently report regarding the gender pay gap at their organization: the unadjusted pay gap, and an adjusted pay gap which only compares workers performing similar roles. It is not reasonable to require that every company can or should achieve an adjusted or unadjusted pay gap of zero, though we would love to see average adjusted pay gaps of zero. The new regulations in the European Union track pay gaps among employee groups larger than 5%, for example. That said, the observed pay gaps at organizations are not centered around zero, as shown from disclosures in the UK, where 63% of companies have gender pay gaps of 5% or more, and in Australia, where 62% of companies do.

Pressure is growing on companies to disclose and narrow their gender pay gaps in the U.S. Our research shows that 48% of the observed gender pay gap among full-time workers is due to factors that companies directly influence — pay equity and opportunity equity.

Through ongoing workplace equity analyses throughout the employee lifecycle, organizations can identify specific issues and hotspots that will allow them to both communicate why their gender pay gap is what it is, and to develop a plan to close that pay gap by closing pay and opportunity gaps. Syndio’s Workplace Equity Analytics Platform can help by performing statistics at scale to identify where and how your organization should invest to create and maintain a truly equitable workplace.

Want to understand where your organization’s pay gaps currently stand? Use our pay gap calculator below.

The information provided herein does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice. All information, content, and materials are provided for general informational purposes only. The links to third-party or government websites are offered for the convenience of the reader; Syndio is not responsible for the contents on linked pages.